The Lesson of the Kick Game

What a simple game taught me about overcoming the fear of failure in new endeavors.

Wrestlers are known for many things, but finesse and dexterity are typically not on the list. Flying elbows? Maybe. Ball handling skills? Maybe not. Yet, somehow, it was by a bunch of wrestlers playing a soccer-oriented warmup game (dubbed the Kick Game, by an effort of great ingenuity) that I began to understand the mechanics of overcoming the anxiety in new pursuits. As I embark on a journey in public writing, I am reminded that the opportunity to grow is earned by the willingness to fail.

Warming Up with the Kick Game

I encountered the Kick Game in the gritty wrestling room at the University of Wyoming in the late 2010’s. Practice started promptly at 3:00, and if you weren’t ready by 2:45, you were late. To pass the time, many of the athletes that arrived on time would line up in the center of the room to play a game.

The mechanics of the Kick Game were simple. Players begin in a line. The first person must kick a ball off of the opposite wall above a certain height without allowing it to touch the ground before it made contact. He then races to the back of the line and the next player is allowed a single bounce before they, too, must return the ball to the wall above the threshold. Players may touch the ball multiple times (no hands!) before the ball reaches its target, so juggling and other airborne ball handling is permitted. Any infraction against these rules constitutes a strike. Three strikes and you’re out. Last person in line wins.

These were, at least, the original version of the rules. Over time they were modified to accommodate our specific circumstances. It was soon decided, for instance, that if a ball contacts the ceiling prior to the front wall, the kicker immediately accumulates three strikes and is ejected from the game. Such a drastic penalty certainly affected the character of the gameplay, but it was necessary. The rule was added after an incident where someone (not to name any names…) blasted a soccer ball into a fire sprinkler, severing it and releasing a torrent directly onto the mats. After an hour of delay, numerous trash cans full of water, and a visit by the facilities staff, practice could finally begin.

Now, those who know me probably recognize that a game requiring any degree of finesse and coordination is not in my wheelhouse. I am a big guy, rather clumsy at times, with two, size 14, left feet. Nevertheless, every day before practice, I found myself in line ready to receive another lesson in humility at the hands of more agile men.

Eventually my games grew longer. Once I had learned how to kick the ball at the wall without hitting the ceiling, I could last a few rounds. Once I honed the ability to catch the ball with a chest bump, and later, to juggle, I could last longer still. I was far from winning the game, but at least now I was playing. The process of improvement drove me onwards. By the end of the season, I was nearly competitive.

I sometimes wonder why I kept getting back in line. I am certain that I looked ridiculous every time I flailed and catapulted the ball into the ceiling. Why prolong the embarrassment? Maybe I was drawn to the floor by FOMO; maybe it was boredom. Perhaps I simply enjoyed competing and the process of improvement. When I was eliminated, it always irked me that I had to wait for the next round. Ultimately, I had determined that the cost of failure (making a fool of myself before my peers) was smaller than the value I received from playing the game. By stepping back in line after each failure, I earned the opportunity to improve my skills.

Deciding when to Shoot

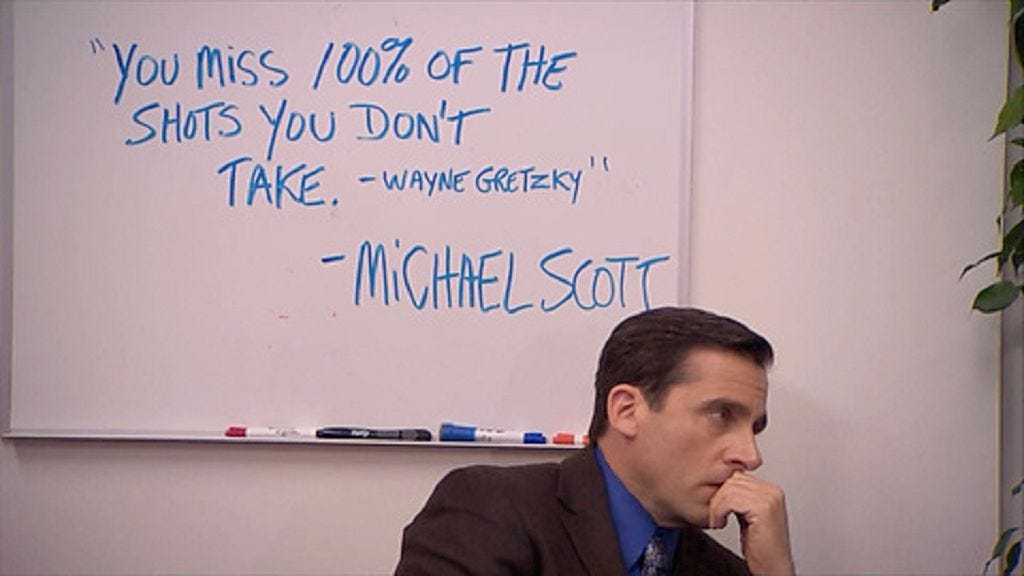

This is starting to sound familiar, as if I’m adding my own name behind the tired Wayne Gretzky quote. After all, “You miss 100% of the shots…”

The statement is as true as its inverted counterpart: “you make 100% of the shots you don’t take.” It’s the hockey-themed equivalent of the cup half-empty—as if pessimists score fewer goals than optimists in a hypothetical shootout. But in the real world, missing 100% of all the shots you take is embarrassing and can have real consequences.

While it is sometimes construed as irrational, the fear of failure is often firmly grounded in reality. Failing important exams can alter a career. Failing in a relationship can cause heartbreak. Failing to bring lunch to work can result in eating too many burritos from the taco truck.

Shooting wildly without counting the costs of failure is irresponsible. Sometimes it really is better to just pass the puck. But when is that the case?

We all recognize that the sentiment behind Gretzky’s quote isn’t to take reckless shots. If what he means is that the probability of scoring is 0% if you never shoot, he is absolutely correct. You can run sprints and do drills, but the only way to actually score is to confront the possibility of failure, take the risk, and shoot.

A Value Function for Engagement

The point is not to ignore legitimate fears. Rather, it recognizes people will take risks when the expected payoff is greater than the expected cost. They earn the opportunity to participate and grow by weighing the costs and accepting the possibility of failure.

I prefer to think of this a simple equation. Let’s say that the total value of participating in some activity is V = S - F, where S = s + s + s +… is the accumulated value of successes, and F = f + f + f +… is the accumulated value of failures. People will continue to engage in an activity when V > 0.

I want to make some brief comments about the equation above. First, I am considering S and F to include all outcomes from an activity where success or failure is a binary classification. Both successes and failures can occur in varied degrees and differing forms so, for the sake of clarity, we say that any success must be valued s ≥ 0 and any failure must be valued f < 0. One could equivalently write our expression as V = v + v + v +…, where v can be any real value. Moreover, we can also include external factors into the value equation—the activity x may be good exercise, which may count as a success. Alternatively, x may take time away from other things, which may count as a failure. All of these things factor together into the equation.

In technical literature, this type of equation is known as a value (or cost) function and it is fundamental concept in the field of artificial intelligence and, especially, in the sub-category of reinforcement learning. The policies of artificial agents are trained by maximizing the reward that they generate through carefully designed value functions. Some researchers, in fact, have suggested that reward is enough to generate intelligence in both machines and humans.

I propose that our value function elicits three potential strategies to reduce the intimidation faced when considering unfamiliar challenges. 1. Increase the average value of successes s, 2. decrease the average cost of failures f, and 3. increase the frequency of success.

Increase the Value of Success

While extrinsic values like money, achievement, and social recognition are generally outside of the scope of influence for a participant, the value of success can be increased by modifying one’s perception of it. This is tantamount to increasing the weight ascribed to intrinsic benefits like growth, enjoyment, and relationships.

Obviously, there was little to gain for me by playing the Kick Game. Even if there had been some kind of external reward for winning, my subpar performance suggests that I would not have benefitted from it anyway. I was able to enjoy the game despite repeated failures because I valued playing the game itself, the process of growing, and the people I played with. Success in the Kick Game was not in the winning, but in the participation.

Decrease the Cost of Failure

One of the most direct approaches to reducing the cost of failure is to ensure that you participate in the appropriate forum. In other words, it is best to start off easy. Beginners are not suited for advanced or even intermediate leagues. White belt martial artists should not be put to compete against black belts.

Of course this is intuitive, but I am mainly preaching to myself. Whenever I consider trying something new, I have a tendency to aspire to perform at a high level from the offset. Somehow, then, I am surprised when I feel intimidated at the prospect of competing out of my league. Because there were extremely low stakes in the Kick Game, I felt comfortable to compete even though I was terrible at the game. The perceived value of succeeding was low, but the cost of failure was even lower still.

I have also found this part of the lesson to be valuable in the context of coaching and teaching. To help new athletes and students excel, creating an environment where they feel safe to test their limits and attempt new skills at full capacity is imperative. The way that a mentor responds to a pupil after a failure is critical for their will to persist in training.

Increase the Probability of Succeeding

If it still uncomfortable to partake in the new pursuit, then it is time to employ the perfectionist’s favorite strategy—practice. By carefully training the new skills in a separate, controlled environment, practice reduces the likelihood of failure by improving performance.

However, it is important to remember that practice comes with a hidden cost. It takes time, and time is a constrained resource. Therefore, unless the process of practicing has some intrinsic value, then practicing, itself, might reduce the total value of the activity until the skills have improved enough to tip the scales back in the other direction.

Thankfully, if it is done in the right environment and with the right intentions, participation is good practice on its own. I never practiced Kick Game specific skills outside of the game—it wasn’t worth my time. I just got back in line with each new game and found myself improving naturally. I had earned the opportunity to improve by accepting the possibility of failure.

Starting Out Somewhere

So, what’s the point?

I find the fear of failure to be ironic. By preventing me from taking risks and gaining genuine experience in the thing that I want to do, it eliminates many opportunities to improve my performance and bolster my confidence. It is a self-perpetuating cycle.

I chose this topic for my first post because writing in public feels like stepping in line for the Kick Game. Somehow, I have decided that I want to play, but I sense that I am far from the proficiency I desire. I feel the burden of inadequacy whenever I contemplate writing my first pieces, and I worry that I will make a fool of myself by dabbling in a craft where I have no business.

But the simple lessons I learned from playing a trivial pre-practice warmup game encourage me. In my internal value function, I have decided that writing and the discipline it teaches are worth the growing pains of a writer. I have situated myself in a forum with low consequences and (for me, anyway) low readership, and therefore low cost of failure. By committing to writing under these conditions, I am giving myself the ability to practice through participation. I suspect that, one day, I will look back on this post and cringe… and see just how far I’ve come.

A Real Photograph of a Real Thing

The onset of Generative AI threatens to desensitize our experience of the radiant beauty reflected in physical reality. In revolt against the trend, with each post I will display a real photograph generated, not by the marching of bits of a mechanical brain, but via the reflection and refraction of light on and through physical media that once was and may one day no longer be.

Today’s photograph is of Channeled Wrack (Pelvetia Canaliculata) growing on gray stone in the coastal tidepools of Northern Ireland.

The sense of the image is, to me, reminiscent of abstract artwork. It evokes more of a feeling than a specific memory or scene. Somehow, I tend to gravitate towards images of such a quality; I have an affinity towards abstraction in many aspects of life. The yellow-brown wrack stands stark against the gray-blue stone and reminds me of cooler weather and the onset of winter, which seems appropriate at Thanksgiving.